The core belief for the Penghayat Percaya is summarized in the philosophy of “Manungaling Kawula Gusti” a principle that humans can meet God through natural knowledge to distinguish between good and bad and wise and unwise. This philosophy is a moral compass in building relationships with fellow humans, living creatures, and the universe. Maintaining ecological harmony is believed to be a way to feel the presence of God, where humans and nature are an inseparable unity. This view is in line with Tynan (2023) on the importance of relationships between entities, while also reflecting the concept of “more-than-human solidarity” raised by Parker and Paudel (2021) in the context of multispecies justice in the climate crisis.

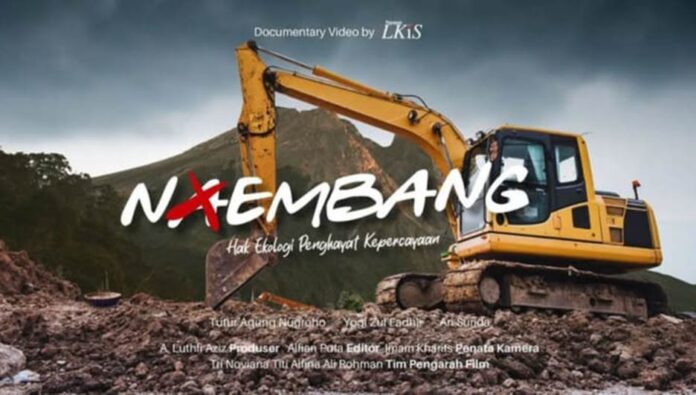

However, this spiritual and ecological harmony is disturbed. The Institute for Islamic and Social Studies (LKiS) with the support of the Indonesian Justice and Peace Foundation (YKPI) raised the deep concerns of the Merapi Belief Adherents community in a short film entitled “Nembang: Ecological Rights of Belief Adherents” which was launched on June 3, 2025 via the Youtube channel. This film records their struggle to defend ecological rights that are threatened by the pressures of modernization, land conversion, and most crucially: illegal mining activities. For adherents, caring for nature is not just an act of conservation, but an integral part of their beliefs and appreciation of ancestral teachings. This film is evidence of how spiritual beliefs that are one with nature have turned into a force of resistance, as well as a loud call for ecological justice and religious freedom.

The impact of the ecological crisis caused by mining is felt very concretely. Teguh, one of the believers, described the severe damage to sacred ritual sites and the surrounding environment. Access to ritual sites is also hampered, often requiring “permission” from the mine guard. The right to learn for students of believers is being taken away because practical learning in the community, which is an important source of assessment, can no longer be carried out. The impact extends to the daily lives of residents: roads are badly damaged, clean water sources are polluted (cloudy and unfit for consumption during the rainy season, dry and cloudy during the dry season), disrupting water supplies to other areas.

Communication efforts by residents, including believers, with mine managers to convey complaints and find joint solutions have been hampered. The government also seems to be ignoring it. In response, residents, spearheaded by the believers community, held the “Umbul Donga” ritual ahead of Ramadan. This ritual is not just a tradition, but an expression of deep love for nature and a form of spiritual resistance to maintain it. This is an effort to get closer to nature while strengthening the commitment to protect it.

In the consolidation discussion, the concerns of the spiritual community became clearer. Mining activities are still massive, often guarded by thugs who carry out repressive practices against residents. Mining permits that were initially legal are increasingly seen as “arbitrary” and illegal. Government mediation remains absent. Fear of repression makes it difficult to make official reports. In addition, limited knowledge and digital communication skills prevent them from voicing this issue in public spaces and on social media. They really hope for support to raise this issue, either through documentaries such as “Nembang” or writings. This response is in line with the findings of Parker and Paudel (2021) on the importance of trans-local alliances for climate justice.

The film “Nembang: Ecological Rights of Belief Adherents” is an important window to understand the complexity of this issue. It not only reveals the violation of ecological rights, but also how environmental destruction is a direct attack on the spiritual identity, religious freedom, and local wisdom of the Belief Adherents community. Their struggle on the slopes of Merapi is a powerful reminder: ecological justice and the sustainability of spiritual traditions are two inseparable things. Protection of belief adherents also means protection of the nature that is their living space and place of worship.

Their struggle is a reminder: “Ecological and spiritual justice are two sides of the same coin.” As Parker and Paudel (2021) emphasize, the climate crisis demands recognition of ecological rights as an integral part of multispecies justice.

References:

- Parker, L.A. & Paudel, D. (2021). More-than-human solidarity and multispecies justice in the climate crisis. Cultural Geographies. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14744740211029287

- Tynan, L. (2023). [Relationality in Indigenous Research].

- LKiS & YKPI. (2025). Nembang: Hak Ekologi Penghayat Kepercayaan. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xc0W0rpku5k

- Laporan Kegiatan LKiS & YKPI (April, 2025)